Tour Outline (abbreviated): (click on pictures to toggle size) If you shake off the somberness, the famous

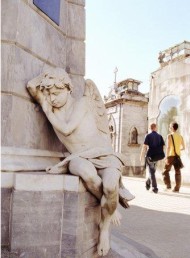

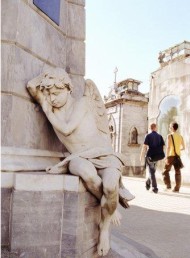

Recoleta Cemetery Tours are a VERY interesting walk. Lots of stories, lots of things to think about: The Recoleta Cemetery Tours are located in the exclusive Recoleta neighbourhood. The Cementery includes graves of some of the most influential and important persons of Argentina, including several presidents, scientists, and wealthy characters. Internationaly, Eva ("Evita") Peron is one of the best known persons buried in this cementery. The entrance to the cemetery is through neo-classical gates with tall Greek columns. The cemetery contains many elaborate marble mausoleums, decorated with statues, in a wide variety of architectural styles. The entire cemetery is laid out in sections like city blocks, with wide tree-lined main walkways branching into sidewalks filled with mausoleums.

Our Recoleta Cemetery Tours show one of the world's extraordinary graveyards, a study in architecture and sculpture, a country's history, mores and soul. A number of tombs are national historic monuments. It is a place of spiritual beauty and extravagant taste. And thanks to Madonna and Broadway, it is hotter than ever as a tourist attraction. Travelers stream through the portal, cameras in hand, and ask the custodians the way to ''Evita.'' (Some even ask for ''Madonna''!).

While many of the mausoleums are in fine shape and well-maintained, others have fallen into disrepair. Several can be found with broken glass, littered with rubbish, and on occasion you might find a mausoleum being used as a janitorial supply closet, with cleaning and maintenance products stored on top of coffins. Each mausoleum bears the family name etched into the facade; brass or bronze plaques are added to the front for particular family members. La Recoleta is one of those cemeteries where the tradition of engraving a death date but no birth date has been maintained.

Every day, busloads of tourists visit the black granite tomb of Evita Peron at Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. They listen to a few words from their tour guide, snap pictures and move on, rarely stopping to appreciate the grandeur of one of the world's most significant graveyards.

Sitting on a four-block area of the city's most expensive real estate, the 183-year-old cemetery is in grave need of restoration.

Marble tombs are being eaten away by acid rain, and their stucco ornaments are also dissolving, exposing brick interiors. Some historically significant tombs are being destroyed by human hands, through neglect or modernization.

This is one of the five most important cemeteries in the world as Recoleta represents an important historical moment for the city of Buenos Aires (one ot the ten largest cities in the world) and how it was forming at the time.

While the cemetery dates from 1822, most of the elaborate tombs (like little mansions) were built between 1880 and 1910, when Buenos Aires grew rapidly in population and wealth. Many were built by the same sculptors who were working on the city's grand new houses at the time.

Many look like Greek or Egyptian temples, including one that belongs to the wealthy Paz family. Almost two stories high, the black granite tomb is adorned with white marble angles and Masonic symbols such as anchors and Maltese crosses inside circles.

Perhaps the most touching gravesite is the one for Rufina Cambaceres, a 19-year-old woman who was accidentally buried alive by her family after being pronounced dead in 1902. (Hearing noises coming from the tomb, graveyard workers opened it and found scratch marks that indicated she had been trying to claw her way out before expiring.) A white marble sculpture of the girl shows her holding the tomb's door and looking out at passers- by with a tearful expression.

Not all of the 4,800 -plus tombs can be restored. Only 90 or so are national monuments that the government has the right to fix. While the city of Buenos Aires owns the cemetery grounds, the vast majority of the tombs, including Evita's, are privately controlled.

Evita's tomb is the most-visited site in the cemetery and one of the best maintained. Visitors often leave wreaths of flowers or attach notes to the bronze door; others tape political messages to the smooth stone surface.

How Evita ended up at Recoleta is a bizarre story. Following her death in 1952, President Juan Peron had his wife embalmed and preserved in life-like condition while he planned a monument for her. But after Juan Peron was overthrown in 1955, the military regime stole Evita's body and took it to Milan, where it was buried in a graveyard under a false name. Her body was finally returned to Argentina in 1974 and, two years later, was placed under a layer of steel and concrete in her family's crypt so it would never be stolen again.

Evita aside, the main attractions of Recoleta are the architecture, the grandiose aura, the sense of rubbing shoulders with Argentine history. The cemetery, inaugurated in 1822 and redesigned in 1881, encompasses 13.5 acres. The departed include Argentine presidents and vice presidents, governors, generals, admirals, industrialists, publishers, judges, doctors, professors, writers, poets, scientists -- and their families. Some of them -- Alvear, Dorrego, Pueyrredon -- are familiar from the Buenos Aires streets and plazas that bear their names. Others, such as Jose Estrada, are known from the Literature of Argentina shelves in bookshops. Still others, such as Dufour, Barchiesi, O'Shea, Zoltowska or Breitman, reflect the many facets of Argentine society.

The labyrinthine necropolis is laid out like a town. There is no map and only one sign -- to Mausoleo Sarmiento, a soaring obelisk crowned with a condor. It commemorates the Argentine hero Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, President, writer and educator, who died Sept. 11, 1888. The predominant color is gray.

The entrance is post-colonial in style with four columns, a peristyle and tall wrought-iron gates. Just inside is the main avenue, an address of choice lined with cypress trees, stone benches and some 50 showpiece mausoleums. A towering bronze statue of El Redentor, The Redeemer, is in the center. Along the avenue visitors admire the white marble beauty of Luz Maria Garcia Velloso in a softly draped dress, lying asleep among sculptured roses on a white marble sarcophagus. A bronze ship atop a green column celebrates Adm. Guillermo Brown (an Irish adventurer/corsair who did well in Argentina), who gave ''days of glory and triumph in the year 1814.'' His neighbor, Gen. Tomas Guido, a friend and colleague of the great Libertador General San Martin, is buried in a little stone grotto.

To turn left at The Redeemer, or right for that matter, is to gradually absorb the life of the cemetery. The earliest graves -- one or two predating 1822 -- are simple, unadorned sepulchers, some with a cross. After 1822 there are changing architectural styles. Nineteenth-century neoclassical tombs favor angels and urns, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns. The fin-de-siecle and early 20th-century porteno taste for things European extended from the streets of the city to the plots of the cemetery. Materials and architects were imported from Europe to create increasingly sumptuous monuments.

The 1920 Herlitzka tomb, for example, features Murano glass, gold leaf and an altar of Italian marble. There were crazes for Art Nouveau, Art Deco, the neo-Gothic. Personal tastes and predilections were also expressed. The 1903 Rufina Cambaceres tomb features giant sculptured Art Nouveau orchids and a soulful statue of the young woman. The Herrera-Noble mausoleum, a brown tinted-glass block, is a study in modern design. The tomb of Adolfo Casal has a stone coffin on top of its roof.

The family pantheon of Dorrego-Ortiz Basualdo (1849-1920) is possibly the graveyard's most priceless structure, though it is contested by the huge Leloir's family --important landowners of Nobel prize fame. Rich in stained glass, Italian sculpture and symbolism, it features a virgin lighting a tall seven-branched candelabrum, symbol of spiritual light and salvation.

A "Dolorosa" by the Milanese sculptor Antonio Tantardini, whose work is also in the Buenos Aires Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, adorns the tomb of Juan Facundo Quiroga (1788-1835), the assassinated gaucho caudillo or war chief known as the Tiger of the Plains.

In every graveyard there is a story behind every grave. In Recoleta the stories are those of a nation, and there are some good ones. In 1828 Gen. Juan Lavalle ordered the execution of Gen. Manuel Dorrego, now his neighbor in death. In the biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga by Sarmiento, ''Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism,'' the author portrayed Quiroga as a barbarian. Now they, too, are posthumous neighbors.

One most astonishing story is the attempted Aramburu-Evita cadaver exchange. When Eva Peron died, at age 33 in 1952, her body was embalmed and kept in the General Confederation of Labor headquarters. Gen. Pedro E. Aramburu, a political enemy of the Perons who was de facto President of the junta that ruled Argentina, ordered the kidnapping of her corpse, which was sent in secret to a cemetery in Italy. The Montoneros, a guerrilla group of Peronist loyalists, abducted and executed Aramburu, then kept his remains as ransom for the return of ''Companera'' Evita's. The police recovered Aramburu's body. But when Evita's body didn't show up, the Montoneros later robbed Aramburu's grave. Evita's mummy was eventually sent to Juan Peron in exile in Madrid and later returned to Buenos Aires, restored, and nearly 25 years after her death, in 1976, buried a few blocks from Aramburu. Juan Peron is buried in Cementerio de la Chacarita, a more populist cemetery in the city.

But Recoleta is not only a story of past power and glory. It is a place that is part of Buenos Aires everyday life. Cemetery custodians polish marble, cradle cats, chat on tomb steps and may open tomb doors for travelers who want to see an interior. (A tip is always welcome, but not mandatory.) Many tombs are lovingly personal, with interiors -- visible through windows or doors -- adorned with symbolic objects and mementoes: exquisite lace cloths over a coffin, a cross encrusted with gems. Behind one wrought-iron door there is a broken chair of carved wood and cane. Inside another there is a black and white photograph of a beautiful woman in a white feather boa.

Family, friends, admirers, patriots, visit faithfully. There's usually someone around, and the cemetery is especially busy on weekends. Visitors replenish flowers in vases, polish silver handles on coffins, leave messages, sit and reflect.

Next we visit beautiful Pilar church (amongst the oldest in the city).

Recoleta's Nuestra Senora del Pilar church is a nice reminder that Catholic art is timelessly elegant. The church is mainly white and Navy; simple and pure and has no paintings in the ceilings, but the altar is solid silver (sent from Peru at the time of the colony) and there are numerous examples of beautiful spanish baroque and rococo all around the walls, together with beautiful carvings gifted by the other neighbouring territories at colonial times. Thedre is also an interesting museum inside the church with many antique reliques and books.

Next we visit beautiful Pilar church (amongst the oldest in the city).

Recoleta's Nuestra Senora del Pilar church is a nice reminder that Catholic art is timelessly elegant. The church is mainly white and Navy; simple and pure and has no paintings in the ceilings, but the altar is solid silver (sent from Peru at the time of the colony) and there are numerous examples of beautiful spanish baroque and rococo all around the walls, together with beautiful carvings gifted by the other neighbouring territories at colonial times. Thedre is also an interesting museum inside the church with many antique reliques and books.

As we leave the church, we walk by the current BA Cultural Center, which used to be a Hospice and a House for the Elderly and the Mendicant till quite recently. Before we go into the top of BA Design Center, we can look at the beautiful statues (to Alvear, President and founder of the Radical Party, one of the two largest political parties here), gum trees and the Palais de Glace, which was in its time (1912!) a fore-runner of discos! It was designed to be an ice-skating rink (hence its name: ice palace) and a ballroom and it was one of the first ballrooms to accept the (till then) outcasted tango dance. After the 1950s it became home to the National Art Exhibit.

Now we continue our walk by the large top terrace of Buenos Aires Design Center (it has 13 restaurants on the terrace, and also boasts 76 specialty design & decoration shops in its two levels) towards Plaza Francia park and we pass by the monument donated by the French people to Argentina in 1910 and across the National Museum of Art.

We walk by the side of the museum and we can see to our right the large greek-temple-like massive building of the Law School of the University of Buenos Aires and to our right a beautiful and unique piece of art: the generic flower (Floralis Generica). The 'Floralis Generica' is a gigantic mobile sculpture with a flower shape. It opens with the sunlight and closes during the night. Donated to the city by the arquitect Eduardo Catalano (costed him 5 million dollars), it has six metallic petals of almost 26 meters height. The flower opens by means of a computerized hydraulic device in the morning and closes during the sunset. It is located atop a water mirror, surrounded by a cascade-water fountain. The flower stays completely open during national holidays, Christmas and New Year's Eve. It is beautiful by day and also by night, as it is colourfully iliminated.

We walk by the side of the museum and we can see to our right the large greek-temple-like massive building of the Law School of the University of Buenos Aires and to our right a beautiful and unique piece of art: the generic flower (Floralis Generica). The 'Floralis Generica' is a gigantic mobile sculpture with a flower shape. It opens with the sunlight and closes during the night. Donated to the city by the arquitect Eduardo Catalano (costed him 5 million dollars), it has six metallic petals of almost 26 meters height. The flower opens by means of a computerized hydraulic device in the morning and closes during the sunset. It is located atop a water mirror, surrounded by a cascade-water fountain. The flower stays completely open during national holidays, Christmas and New Year's Eve. It is beautiful by day and also by night, as it is colourfully iliminated.

Next, we will walk by a park with large monuments representing the Uruguayan independence hero Gral. Artigas and across TV Channel 7, broadcast station, to just stroll briefly through one of the nicest and most exclusive neighbourhoods: Palermo chico. Designed in a secluded, labyrinthic way, it resembles a spider web, and its circulation is an esoteric mistery (they say it is purposefully so to deter visitors and kidnappers, which would get entangled in its labyrinthic streets) and without shops to cause any circulation or annoyance. The styles are eclectic and diverse, but all beautiful and comfortable. In here you live at almost no distance from downtown, but unlike the dense highly-populated buildings of Barrio Norte, Belgrano or the other high-level neighbourhoods, here you live like if you were in a private country club: in stand-alone houses, most of them with beautiful inner gardens.

Next, we will walk by a park with large monuments representing the Uruguayan independence hero Gral. Artigas and across TV Channel 7, broadcast station, to just stroll briefly through one of the nicest and most exclusive neighbourhoods: Palermo chico. Designed in a secluded, labyrinthic way, it resembles a spider web, and its circulation is an esoteric mistery (they say it is purposefully so to deter visitors and kidnappers, which would get entangled in its labyrinthic streets) and without shops to cause any circulation or annoyance. The styles are eclectic and diverse, but all beautiful and comfortable. In here you live at almost no distance from downtown, but unlike the dense highly-populated buildings of Barrio Norte, Belgrano or the other high-level neighbourhoods, here you live like if you were in a private country club: in stand-alone houses, most of them with beautiful inner gardens.

Now we go past a replica of the house where San Martin exiled himself in Grand Bourg, France. Jose de San Martin was born on February 25, 1778 in Yapeyu, located in the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata', which is now known as eastern Argentina. In 1784, when San Martin was six years old, the family returned to Spain, where he was educated at the "Seminario de Nobles". He started his military career early serving as an army officer against the forces of Napoleon between 1808 and 1811. Even though San Martin was loyal towards his mother country (Spain) when he fought against Napoleon, he disliked the traditional absolute monarchy and the existing colonial system. In 1811, he decided to resign from Spanish service. After meeting revolutionary Spanish Americans in London, England, he sailed for Buenos Aires, and was almost immediately taken into service in the revolutionary regime. As a very experienced soldier, he was a great asset in the revolutionary movement in South America.

Now we go past a replica of the house where San Martin exiled himself in Grand Bourg, France. Jose de San Martin was born on February 25, 1778 in Yapeyu, located in the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata', which is now known as eastern Argentina. In 1784, when San Martin was six years old, the family returned to Spain, where he was educated at the "Seminario de Nobles". He started his military career early serving as an army officer against the forces of Napoleon between 1808 and 1811. Even though San Martin was loyal towards his mother country (Spain) when he fought against Napoleon, he disliked the traditional absolute monarchy and the existing colonial system. In 1811, he decided to resign from Spanish service. After meeting revolutionary Spanish Americans in London, England, he sailed for Buenos Aires, and was almost immediately taken into service in the revolutionary regime. As a very experienced soldier, he was a great asset in the revolutionary movement in South America.

We will now continue our walk across Av. del Libertador (actually this is an indirect way of addressing San Martin, the libertador) to the Errasuriz Palace.Since 1937, this stunning neoclassical mansion, formerly the Palacio Errazuriz, has operated as a museum devoted to the decorative arts. (It was declared an official historic landmark in 1998.) Built in 1911 by French architect Rene Sergent for a Buenos Aires power couple (Josefina de Alvear and Matias Errazuriz Ortuzar), the house continues to wow visitors by providing a peek into just how good Argentina's filthy rich once had it. But there are also som 4,000 amazing objets to go along with the eye-popping architecture, including an arresting El Greco in the 54-by-64-foot Gran Hall, and two gigantic antique and most valuable tapestries that are attributed to have been the cause this house was built (yes, it is in record that this huge palace was designed around housing this tapestries on the longer wall of its main hall).

We will now continue our walk across Av. del Libertador (actually this is an indirect way of addressing San Martin, the libertador) to the Errasuriz Palace.Since 1937, this stunning neoclassical mansion, formerly the Palacio Errazuriz, has operated as a museum devoted to the decorative arts. (It was declared an official historic landmark in 1998.) Built in 1911 by French architect Rene Sergent for a Buenos Aires power couple (Josefina de Alvear and Matias Errazuriz Ortuzar), the house continues to wow visitors by providing a peek into just how good Argentina's filthy rich once had it. But there are also som 4,000 amazing objets to go along with the eye-popping architecture, including an arresting El Greco in the 54-by-64-foot Gran Hall, and two gigantic antique and most valuable tapestries that are attributed to have been the cause this house was built (yes, it is in record that this huge palace was designed around housing this tapestries on the longer wall of its main hall).

After leaving this Palace, we walk across the Argentine Automobile Club, where we can enter and take a quick look at the antique car museum, which includes the first car built in argentina and a few other amazing cars, including a 1904 Cadillac, you would hardly recognize as such.

After leaving this Palace, we walk across the Argentine Automobile Club, where we can enter and take a quick look at the antique car museum, which includes the first car built in argentina and a few other amazing cars, including a 1904 Cadillac, you would hardly recognize as such.

On exiting the ACA we walk under and into the National Library to take a look at this interesting building while we cross into the stairs of another idiosincratic secluded neighbourhood, only that this one is protected by stairs, cars can't climb! This neighbourhood atop a small hill (Loma Mitre) is situated on land that once belonged to an English entrepreneur (in the 19 century) and he lost it to the bank, and was later reposessed by the government. Ironically, now part of this area is occupied by the English embassy and the neighbouring residence of the English ambassador. When we climb down from the steps by the embassy we are almost back in Recoleta and the design center. Its interesting to mention some Love hotels (an interesting Argentinean feature) as we walk our way into the Recoleta Village area, where our walk ends (or at least we stop walking and sit down for commenting what we just saw over coffee and giving some free advise on other things to see).

The publicly owned National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires is the principal showcase for the art collections of Argentina. Its history appears to be a long struggle between, on the one hand, the desire of art lovers and collectors for an appropriate repository and, on the other, bureaucratic disinterest and inertia. (Recent allegations of corruption and profiteering at the museum's highest level have precipitated an overdue change in its leadership.) As early as 1870, one collector bequeathed fifty paintings to the state on the condition that they be the basis for a museum. Not until 1895 was the museum organized and it opened its first exhibit in rented space in a department store on Christmas day, 1896. By 1908 the collection had grown to nearly 3,500 pieces, but a permanent home for the museum was not achieved for another quarter of a century. The present building, with its strong terra cotta color, opened as the museum in 1933. It was originally a pumping station that took water from the river, filtered it, and moved it on to a storage facility. It's no wonder that the building has more the appearance of a factory (with a neo-classic entryway superimposed) than of a home for a nation's artistic heritage. The museum's collections have now grown to some 11,000 pieces (in 32 galleries), only a small portion of which can be displayed in its relatively small quarters. Covering mostly the 19th and early 20th centuries, both European and Argentine artists are represented, with a token few modern North American works (Pollock, Louise Nevelson). There are works by Rembrandt, Rubens, El Greco, Rodin, Henry Moore, Manet, Van Gogh, Degas, Courbet, Picasso and many others. approximately ten years ago there was a major robbery and many art works were stolen, having recently recovered a few. Art lovers visiting Buenos Aires will want to stop by for an hour's browsing which will likely provide few surprises, but a fair, if limited, share of esthetic pleasures.

The publicly owned National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires is the principal showcase for the art collections of Argentina. Its history appears to be a long struggle between, on the one hand, the desire of art lovers and collectors for an appropriate repository and, on the other, bureaucratic disinterest and inertia. (Recent allegations of corruption and profiteering at the museum's highest level have precipitated an overdue change in its leadership.) As early as 1870, one collector bequeathed fifty paintings to the state on the condition that they be the basis for a museum. Not until 1895 was the museum organized and it opened its first exhibit in rented space in a department store on Christmas day, 1896. By 1908 the collection had grown to nearly 3,500 pieces, but a permanent home for the museum was not achieved for another quarter of a century. The present building, with its strong terra cotta color, opened as the museum in 1933. It was originally a pumping station that took water from the river, filtered it, and moved it on to a storage facility. It's no wonder that the building has more the appearance of a factory (with a neo-classic entryway superimposed) than of a home for a nation's artistic heritage. The museum's collections have now grown to some 11,000 pieces (in 32 galleries), only a small portion of which can be displayed in its relatively small quarters. Covering mostly the 19th and early 20th centuries, both European and Argentine artists are represented, with a token few modern North American works (Pollock, Louise Nevelson). There are works by Rembrandt, Rubens, El Greco, Rodin, Henry Moore, Manet, Van Gogh, Degas, Courbet, Picasso and many others. approximately ten years ago there was a major robbery and many art works were stolen, having recently recovered a few. Art lovers visiting Buenos Aires will want to stop by for an hour's browsing which will likely provide few surprises, but a fair, if limited, share of esthetic pleasures.

![]() Description: Scroll (way) down for extensive information!

Description: Scroll (way) down for extensive information!![]() When: 1 pm daily 365 days a year, rain or shine --Just show-up, though booking/calling ahead is advisable as walks may fill-up or be cancelled

When: 1 pm daily 365 days a year, rain or shine --Just show-up, though booking/calling ahead is advisable as walks may fill-up or be cancelled![]() Duration: 2 hours (approximately)

Duration: 2 hours (approximately)![]() Price: US$37.50 p/p

Price: US$37.50 p/p![]() Discounts: Each 6 people, one is free of charge (18% discount)

Discounts: Each 6 people, one is free of charge (18% discount)![]() Meet: Corner of 598 Quintana Av., near payphones and large tree, outside 'La Biela' cafe. Look for our guides, wearing 'BA-Walking-Tours' jackets, shirts or baseball caps. Get printable, bilingual ('good-for-taxi' or asking) directions here, or see map here.

Meet: Corner of 598 Quintana Av., near payphones and large tree, outside 'La Biela' cafe. Look for our guides, wearing 'BA-Walking-Tours' jackets, shirts or baseball caps. Get printable, bilingual ('good-for-taxi' or asking) directions here, or see map here. ![]() Note: After this ultra-enjoyable walk you will understand Buenos Aires (and Argentina!!) much better. It includes over 25 main city landmarks (different from our other walks). This is not a strenuous walk. At some point (time permitting) we may stop for coffee or refreshments at some emblematic cafe of cultural or historical value. Snacks, drinks, hotel pickup, transportation, foot massage, mid-life-counseling, good sense of humour and gratuities are not included (actually massage, counseling and good sense of humour are not even available!).

Note: After this ultra-enjoyable walk you will understand Buenos Aires (and Argentina!!) much better. It includes over 25 main city landmarks (different from our other walks). This is not a strenuous walk. At some point (time permitting) we may stop for coffee or refreshments at some emblematic cafe of cultural or historical value. Snacks, drinks, hotel pickup, transportation, foot massage, mid-life-counseling, good sense of humour and gratuities are not included (actually massage, counseling and good sense of humour are not even available!).![]() Some key sights:

Some key sights:

Our Recoleta Cemetery Tours show one of the world's extraordinary graveyards, a study in architecture and sculpture, a country's history, mores and soul. A number of tombs are national historic monuments. It is a place of spiritual beauty and extravagant taste. And thanks to Madonna and Broadway, it is hotter than ever as a tourist attraction. Travelers stream through the portal, cameras in hand, and ask the custodians the way to ''Evita.'' (Some even ask for ''Madonna''!).

Our Recoleta Cemetery Tours show one of the world's extraordinary graveyards, a study in architecture and sculpture, a country's history, mores and soul. A number of tombs are national historic monuments. It is a place of spiritual beauty and extravagant taste. And thanks to Madonna and Broadway, it is hotter than ever as a tourist attraction. Travelers stream through the portal, cameras in hand, and ask the custodians the way to ''Evita.'' (Some even ask for ''Madonna''!).

Every day, busloads of tourists visit the black granite tomb of Evita Peron at Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. They listen to a few words from their tour guide, snap pictures and move on, rarely stopping to appreciate the grandeur of one of the world's most significant graveyards.

Sitting on a four-block area of the city's most expensive real estate, the 183-year-old cemetery is in grave need of restoration.

Marble tombs are being eaten away by acid rain, and their stucco ornaments are also dissolving, exposing brick interiors. Some historically significant tombs are being destroyed by human hands, through neglect or modernization.

This is one of the five most important cemeteries in the world as Recoleta represents an important historical moment for the city of Buenos Aires (one ot the ten largest cities in the world) and how it was forming at the time.

Every day, busloads of tourists visit the black granite tomb of Evita Peron at Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. They listen to a few words from their tour guide, snap pictures and move on, rarely stopping to appreciate the grandeur of one of the world's most significant graveyards.

Sitting on a four-block area of the city's most expensive real estate, the 183-year-old cemetery is in grave need of restoration.

Marble tombs are being eaten away by acid rain, and their stucco ornaments are also dissolving, exposing brick interiors. Some historically significant tombs are being destroyed by human hands, through neglect or modernization.

This is one of the five most important cemeteries in the world as Recoleta represents an important historical moment for the city of Buenos Aires (one ot the ten largest cities in the world) and how it was forming at the time.

The labyrinthine necropolis is laid out like a town. There is no map and only one sign -- to Mausoleo Sarmiento, a soaring obelisk crowned with a condor. It commemorates the Argentine hero Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, President, writer and educator, who died Sept. 11, 1888. The predominant color is gray.

The entrance is post-colonial in style with four columns, a peristyle and tall wrought-iron gates. Just inside is the main avenue, an address of choice lined with cypress trees, stone benches and some 50 showpiece mausoleums. A towering bronze statue of El Redentor, The Redeemer, is in the center. Along the avenue visitors admire the white marble beauty of Luz Maria Garcia Velloso in a softly draped dress, lying asleep among sculptured roses on a white marble sarcophagus. A bronze ship atop a green column celebrates Adm. Guillermo Brown (an Irish adventurer/corsair who did well in Argentina), who gave ''days of glory and triumph in the year 1814.'' His neighbor, Gen. Tomas Guido, a friend and colleague of the great Libertador General San Martin, is buried in a little stone grotto.

The labyrinthine necropolis is laid out like a town. There is no map and only one sign -- to Mausoleo Sarmiento, a soaring obelisk crowned with a condor. It commemorates the Argentine hero Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, President, writer and educator, who died Sept. 11, 1888. The predominant color is gray.

The entrance is post-colonial in style with four columns, a peristyle and tall wrought-iron gates. Just inside is the main avenue, an address of choice lined with cypress trees, stone benches and some 50 showpiece mausoleums. A towering bronze statue of El Redentor, The Redeemer, is in the center. Along the avenue visitors admire the white marble beauty of Luz Maria Garcia Velloso in a softly draped dress, lying asleep among sculptured roses on a white marble sarcophagus. A bronze ship atop a green column celebrates Adm. Guillermo Brown (an Irish adventurer/corsair who did well in Argentina), who gave ''days of glory and triumph in the year 1814.'' His neighbor, Gen. Tomas Guido, a friend and colleague of the great Libertador General San Martin, is buried in a little stone grotto.

In every graveyard there is a story behind every grave. In Recoleta the stories are those of a nation, and there are some good ones. In 1828 Gen. Juan Lavalle ordered the execution of Gen. Manuel Dorrego, now his neighbor in death. In the biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga by Sarmiento, ''Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism,'' the author portrayed Quiroga as a barbarian. Now they, too, are posthumous neighbors.

One most astonishing story is the attempted Aramburu-Evita cadaver exchange. When Eva Peron died, at age 33 in 1952, her body was embalmed and kept in the General Confederation of Labor headquarters. Gen. Pedro E. Aramburu, a political enemy of the Perons who was de facto President of the junta that ruled Argentina, ordered the kidnapping of her corpse, which was sent in secret to a cemetery in Italy. The Montoneros, a guerrilla group of Peronist loyalists, abducted and executed Aramburu, then kept his remains as ransom for the return of ''Companera'' Evita's. The police recovered Aramburu's body. But when Evita's body didn't show up, the Montoneros later robbed Aramburu's grave. Evita's mummy was eventually sent to Juan Peron in exile in Madrid and later returned to Buenos Aires, restored, and nearly 25 years after her death, in 1976, buried a few blocks from Aramburu. Juan Peron is buried in Cementerio de la Chacarita, a more populist cemetery in the city.

In every graveyard there is a story behind every grave. In Recoleta the stories are those of a nation, and there are some good ones. In 1828 Gen. Juan Lavalle ordered the execution of Gen. Manuel Dorrego, now his neighbor in death. In the biography of Juan Facundo Quiroga by Sarmiento, ''Facundo: Civilization and Barbarism,'' the author portrayed Quiroga as a barbarian. Now they, too, are posthumous neighbors.

One most astonishing story is the attempted Aramburu-Evita cadaver exchange. When Eva Peron died, at age 33 in 1952, her body was embalmed and kept in the General Confederation of Labor headquarters. Gen. Pedro E. Aramburu, a political enemy of the Perons who was de facto President of the junta that ruled Argentina, ordered the kidnapping of her corpse, which was sent in secret to a cemetery in Italy. The Montoneros, a guerrilla group of Peronist loyalists, abducted and executed Aramburu, then kept his remains as ransom for the return of ''Companera'' Evita's. The police recovered Aramburu's body. But when Evita's body didn't show up, the Montoneros later robbed Aramburu's grave. Evita's mummy was eventually sent to Juan Peron in exile in Madrid and later returned to Buenos Aires, restored, and nearly 25 years after her death, in 1976, buried a few blocks from Aramburu. Juan Peron is buried in Cementerio de la Chacarita, a more populist cemetery in the city.

But Recoleta is not only a story of past power and glory. It is a place that is part of Buenos Aires everyday life. Cemetery custodians polish marble, cradle cats, chat on tomb steps and may open tomb doors for travelers who want to see an interior. (A tip is always welcome, but not mandatory.) Many tombs are lovingly personal, with interiors -- visible through windows or doors -- adorned with symbolic objects and mementoes: exquisite lace cloths over a coffin, a cross encrusted with gems. Behind one wrought-iron door there is a broken chair of carved wood and cane. Inside another there is a black and white photograph of a beautiful woman in a white feather boa.

Family, friends, admirers, patriots, visit faithfully. There's usually someone around, and the cemetery is especially busy on weekends. Visitors replenish flowers in vases, polish silver handles on coffins, leave messages, sit and reflect.

But Recoleta is not only a story of past power and glory. It is a place that is part of Buenos Aires everyday life. Cemetery custodians polish marble, cradle cats, chat on tomb steps and may open tomb doors for travelers who want to see an interior. (A tip is always welcome, but not mandatory.) Many tombs are lovingly personal, with interiors -- visible through windows or doors -- adorned with symbolic objects and mementoes: exquisite lace cloths over a coffin, a cross encrusted with gems. Behind one wrought-iron door there is a broken chair of carved wood and cane. Inside another there is a black and white photograph of a beautiful woman in a white feather boa.

Family, friends, admirers, patriots, visit faithfully. There's usually someone around, and the cemetery is especially busy on weekends. Visitors replenish flowers in vases, polish silver handles on coffins, leave messages, sit and reflect.

Next we visit beautiful Pilar church (amongst the oldest in the city).

Recoleta's Nuestra Senora del Pilar church is a nice reminder that Catholic art is timelessly elegant. The church is mainly white and Navy; simple and pure and has no paintings in the ceilings, but the altar is solid silver (sent from Peru at the time of the colony) and there are numerous examples of beautiful spanish baroque and rococo all around the walls, together with beautiful carvings gifted by the other neighbouring territories at colonial times. Thedre is also an interesting museum inside the church with many antique reliques and books.

Next we visit beautiful Pilar church (amongst the oldest in the city).

Recoleta's Nuestra Senora del Pilar church is a nice reminder that Catholic art is timelessly elegant. The church is mainly white and Navy; simple and pure and has no paintings in the ceilings, but the altar is solid silver (sent from Peru at the time of the colony) and there are numerous examples of beautiful spanish baroque and rococo all around the walls, together with beautiful carvings gifted by the other neighbouring territories at colonial times. Thedre is also an interesting museum inside the church with many antique reliques and books.

We walk by the side of the museum and we can see to our right the large greek-temple-like massive building of the Law School of the University of Buenos Aires and to our right a beautiful and unique piece of art: the generic flower (Floralis Generica). The 'Floralis Generica' is a gigantic mobile sculpture with a flower shape. It opens with the sunlight and closes during the night. Donated to the city by the arquitect Eduardo Catalano (costed him 5 million dollars), it has six metallic petals of almost 26 meters height. The flower opens by means of a computerized hydraulic device in the morning and closes during the sunset. It is located atop a water mirror, surrounded by a cascade-water fountain. The flower stays completely open during national holidays, Christmas and New Year's Eve. It is beautiful by day and also by night, as it is colourfully iliminated.

We walk by the side of the museum and we can see to our right the large greek-temple-like massive building of the Law School of the University of Buenos Aires and to our right a beautiful and unique piece of art: the generic flower (Floralis Generica). The 'Floralis Generica' is a gigantic mobile sculpture with a flower shape. It opens with the sunlight and closes during the night. Donated to the city by the arquitect Eduardo Catalano (costed him 5 million dollars), it has six metallic petals of almost 26 meters height. The flower opens by means of a computerized hydraulic device in the morning and closes during the sunset. It is located atop a water mirror, surrounded by a cascade-water fountain. The flower stays completely open during national holidays, Christmas and New Year's Eve. It is beautiful by day and also by night, as it is colourfully iliminated.

Next, we will walk by a park with large monuments representing the Uruguayan independence hero Gral. Artigas and across TV Channel 7, broadcast station, to just stroll briefly through one of the nicest and most exclusive neighbourhoods: Palermo chico. Designed in a secluded, labyrinthic way, it resembles a spider web, and its circulation is an esoteric mistery (they say it is purposefully so to deter visitors and kidnappers, which would get entangled in its labyrinthic streets) and without shops to cause any circulation or annoyance. The styles are eclectic and diverse, but all beautiful and comfortable. In here you live at almost no distance from downtown, but unlike the dense highly-populated buildings of Barrio Norte, Belgrano or the other high-level neighbourhoods, here you live like if you were in a private country club: in stand-alone houses, most of them with beautiful inner gardens.

Next, we will walk by a park with large monuments representing the Uruguayan independence hero Gral. Artigas and across TV Channel 7, broadcast station, to just stroll briefly through one of the nicest and most exclusive neighbourhoods: Palermo chico. Designed in a secluded, labyrinthic way, it resembles a spider web, and its circulation is an esoteric mistery (they say it is purposefully so to deter visitors and kidnappers, which would get entangled in its labyrinthic streets) and without shops to cause any circulation or annoyance. The styles are eclectic and diverse, but all beautiful and comfortable. In here you live at almost no distance from downtown, but unlike the dense highly-populated buildings of Barrio Norte, Belgrano or the other high-level neighbourhoods, here you live like if you were in a private country club: in stand-alone houses, most of them with beautiful inner gardens.

Now we go past a replica of the house where San Martin exiled himself in Grand Bourg, France. Jose de San Martin was born on February 25, 1778 in Yapeyu, located in the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata', which is now known as eastern Argentina. In 1784, when San Martin was six years old, the family returned to Spain, where he was educated at the "Seminario de Nobles". He started his military career early serving as an army officer against the forces of Napoleon between 1808 and 1811. Even though San Martin was loyal towards his mother country (Spain) when he fought against Napoleon, he disliked the traditional absolute monarchy and the existing colonial system. In 1811, he decided to resign from Spanish service. After meeting revolutionary Spanish Americans in London, England, he sailed for Buenos Aires, and was almost immediately taken into service in the revolutionary regime. As a very experienced soldier, he was a great asset in the revolutionary movement in South America.

Now we go past a replica of the house where San Martin exiled himself in Grand Bourg, France. Jose de San Martin was born on February 25, 1778 in Yapeyu, located in the viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata', which is now known as eastern Argentina. In 1784, when San Martin was six years old, the family returned to Spain, where he was educated at the "Seminario de Nobles". He started his military career early serving as an army officer against the forces of Napoleon between 1808 and 1811. Even though San Martin was loyal towards his mother country (Spain) when he fought against Napoleon, he disliked the traditional absolute monarchy and the existing colonial system. In 1811, he decided to resign from Spanish service. After meeting revolutionary Spanish Americans in London, England, he sailed for Buenos Aires, and was almost immediately taken into service in the revolutionary regime. As a very experienced soldier, he was a great asset in the revolutionary movement in South America.

We will now continue our walk across Av. del Libertador (actually this is an indirect way of addressing San Martin, the libertador) to the Errasuriz Palace.Since 1937, this stunning neoclassical mansion, formerly the Palacio Errazuriz, has operated as a museum devoted to the decorative arts. (It was declared an official historic landmark in 1998.) Built in 1911 by French architect Rene Sergent for a Buenos Aires power couple (Josefina de Alvear and Matias Errazuriz Ortuzar), the house continues to wow visitors by providing a peek into just how good Argentina's filthy rich once had it. But there are also som 4,000 amazing objets to go along with the eye-popping architecture, including an arresting El Greco in the 54-by-64-foot Gran Hall, and two gigantic antique and most valuable tapestries that are attributed to have been the cause this house was built (yes, it is in record that this huge palace was designed around housing this tapestries on the longer wall of its main hall).

We will now continue our walk across Av. del Libertador (actually this is an indirect way of addressing San Martin, the libertador) to the Errasuriz Palace.Since 1937, this stunning neoclassical mansion, formerly the Palacio Errazuriz, has operated as a museum devoted to the decorative arts. (It was declared an official historic landmark in 1998.) Built in 1911 by French architect Rene Sergent for a Buenos Aires power couple (Josefina de Alvear and Matias Errazuriz Ortuzar), the house continues to wow visitors by providing a peek into just how good Argentina's filthy rich once had it. But there are also som 4,000 amazing objets to go along with the eye-popping architecture, including an arresting El Greco in the 54-by-64-foot Gran Hall, and two gigantic antique and most valuable tapestries that are attributed to have been the cause this house was built (yes, it is in record that this huge palace was designed around housing this tapestries on the longer wall of its main hall).

After leaving this Palace, we walk across the Argentine Automobile Club, where we can enter and take a quick look at the antique car museum, which includes the first car built in argentina and a few other amazing cars, including a 1904 Cadillac, you would hardly recognize as such.

After leaving this Palace, we walk across the Argentine Automobile Club, where we can enter and take a quick look at the antique car museum, which includes the first car built in argentina and a few other amazing cars, including a 1904 Cadillac, you would hardly recognize as such.

The publicly owned National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires is the principal showcase for the art collections of Argentina. Its history appears to be a long struggle between, on the one hand, the desire of art lovers and collectors for an appropriate repository and, on the other, bureaucratic disinterest and inertia. (Recent allegations of corruption and profiteering at the museum's highest level have precipitated an overdue change in its leadership.) As early as 1870, one collector bequeathed fifty paintings to the state on the condition that they be the basis for a museum. Not until 1895 was the museum organized and it opened its first exhibit in rented space in a department store on Christmas day, 1896. By 1908 the collection had grown to nearly 3,500 pieces, but a permanent home for the museum was not achieved for another quarter of a century. The present building, with its strong terra cotta color, opened as the museum in 1933. It was originally a pumping station that took water from the river, filtered it, and moved it on to a storage facility. It's no wonder that the building has more the appearance of a factory (with a neo-classic entryway superimposed) than of a home for a nation's artistic heritage. The museum's collections have now grown to some 11,000 pieces (in 32 galleries), only a small portion of which can be displayed in its relatively small quarters. Covering mostly the 19th and early 20th centuries, both European and Argentine artists are represented, with a token few modern North American works (Pollock, Louise Nevelson). There are works by Rembrandt, Rubens, El Greco, Rodin, Henry Moore, Manet, Van Gogh, Degas, Courbet, Picasso and many others. approximately ten years ago there was a major robbery and many art works were stolen, having recently recovered a few. Art lovers visiting Buenos Aires will want to stop by for an hour's browsing which will likely provide few surprises, but a fair, if limited, share of esthetic pleasures.

The publicly owned National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires is the principal showcase for the art collections of Argentina. Its history appears to be a long struggle between, on the one hand, the desire of art lovers and collectors for an appropriate repository and, on the other, bureaucratic disinterest and inertia. (Recent allegations of corruption and profiteering at the museum's highest level have precipitated an overdue change in its leadership.) As early as 1870, one collector bequeathed fifty paintings to the state on the condition that they be the basis for a museum. Not until 1895 was the museum organized and it opened its first exhibit in rented space in a department store on Christmas day, 1896. By 1908 the collection had grown to nearly 3,500 pieces, but a permanent home for the museum was not achieved for another quarter of a century. The present building, with its strong terra cotta color, opened as the museum in 1933. It was originally a pumping station that took water from the river, filtered it, and moved it on to a storage facility. It's no wonder that the building has more the appearance of a factory (with a neo-classic entryway superimposed) than of a home for a nation's artistic heritage. The museum's collections have now grown to some 11,000 pieces (in 32 galleries), only a small portion of which can be displayed in its relatively small quarters. Covering mostly the 19th and early 20th centuries, both European and Argentine artists are represented, with a token few modern North American works (Pollock, Louise Nevelson). There are works by Rembrandt, Rubens, El Greco, Rodin, Henry Moore, Manet, Van Gogh, Degas, Courbet, Picasso and many others. approximately ten years ago there was a major robbery and many art works were stolen, having recently recovered a few. Art lovers visiting Buenos Aires will want to stop by for an hour's browsing which will likely provide few surprises, but a fair, if limited, share of esthetic pleasures.

button to book this tour

button to book this tour